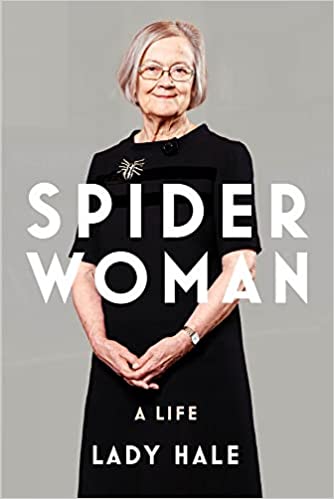

‘Boris the Spider’ is a 1960s song by The Who. About half a century after it was released, another Boris, desperate to avoid the fate of his predecessor, suspended (the legal term is ‘prorogued’) the UK Parliament for five weeks, i.e. two weeks shy of Brexit Day, which was set on 31 October. The idea was to prevent Parliamentary interference in the withdrawal process, and thereby ‘get Brexit done’. The 11-member panel of the Supreme Court that gathered to consider the legality of the Prime Minister’s actions, had as its president Lady Brenda Hale. She delivered the Court’s judgment (annulling prorogation) wearing a dark suit. Pinned on it was an antique silver spider brooch. The ensuing stream of jokes in the news media prompted the title of this memoir.

The book is worth reading just to follow Hale’s off-centre path to the highest legal office in the UK. A Family Lawyer becoming the president of the Supreme Court? It could never happen in India.

Hale’s childhood is spent close to a town called Richmond in North Yorkshire, where her father is the headmaster of the local school. He dies suddenly when she is only thirteen, leaving the family (a mother and three daughters) completely bereft. Hale does not linger over the emptiness of the loss of a parent at an early age, but conveys all in these sparse words:

“What was to become of us? Where would we live? What would we live on? And where would we go to school?”

A few pages on, she has some answers:

“Looking back, I feel sure that the sudden loss of security, and regaining it through our mother’s resourcefulness, is what made me so determined to qualify for a career, to carry on working whether or not I married or had a family, and never to become wholly dependent upon anyone else…”

The names of the three sisters are on the honours board of Richmond School for the years 1955, 1962 and 1963 respectively. Sometimes great setbacks lead to great achievements.

When she is in high school, young Brenda is inspired to study the law after learning ancient stories of lawyers standing up to power-hungry kings (the Brexit judgment appears to have been many years in the making). The sexism of the times means that she can only study in Girton, an all-woman’s college in Cambridge University. From there, she accepts a teaching post at Manchester University, and gets attracted by Family Law. Her work in the field gets her onto mental health and social welfare tribunals. At the young age of 39, she applies for, and is appointed on the Law Commission, becoming the first woman commissioner. Her focus, again, is family law.

The UK Law Commission’s work during Hale’s time (the early 80s), reads like a wish list for social law reform in the India of today – abolishing blasphemy as a crime, modernising child care law (custody, access, guardianship, wards of the court), guardianship of the mentally incapacitated, and introducing irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a ground for divorce. A lot of the work she does on the Law Commission ends in failure and frustration, only to find success a few decades later. In her words, “Never say never in law reform”. Maybe there is hope for us Indians as well?

Until the end of her time at the Law Commission, Hale’s judicial prospects resemble a planet careening dangerously away from its orbit – the chances of landing a seat on the highest court in the land seem a laughable impossibility. But in 1993, we are back on course. She gets offered a seat on the High Court (the Family Division). For someone like me, with modest experience in family law, Hale’s perspective on the divergence in judicial approach from any other law is a revelation:

“The sorts of decisions which family judges have to make are quite different from the decisions made in criminal and civil cases. There, it is mostly about finding out what went on in the past and imposing the appropriate punishment for a crime or the appropriate compensation for a breach of contract or a civil wrong. It is not usually about managing the future relations between the parties. In family cases, it may be necessary to find out what went on in the past, but this is always as a preliminary to managing the family’s future. It is necessary to be sensitive to the whole family context, its religious and cultural background, as well as the personalities of each of the people involved, including their children. It is necessary to be sensitive to what the children are saying…It is necessary to try and create an atmosphere in court which reduces the tension rather than ramps it up, making it more rather than less likely that agreements can be reached. It is necessary to smile.”

Hale’s tryst with family law ends with her promotion to the Court of Appeal. From there she becomes, to her eternal glory, the first (and only) woman to sit in the House of Lords. The reason for this is that the jurisdiction of the House of Lords was transferred to the newly minted UK Supreme Court. Hale’s account of the process of picking and furnishing the right building for the SC is absorbing.

Here, a small digression. Until reading this book, I didn’t know that hanging in the UK SC are two portraits of Indians. They are (you would never guess) Sir Shadi Lal, from the 1930s Privy Council, and Cornelia Sorabji (the first woman to study law at Oxford). I found the portrait of Sir Shadi Lal to be particularly handsome, though somewhat ostentatious – he wears a dark blue high-collar jacket with gold oak leaf embroidery on the chest and cuffs to match his gold rimmed spectacles, white breeches to go with his white gloves, and holds a cocked hat with ostrich feathers on his lap. He is easily recognisable as the man who self-indulgently had the letters ‘SL’ inscribed as the finials on the metallic railings of his sprawling bungalow in Lahore (it still stands). Hale only refers to him as ‘the one darker-skinned man’ among ‘the many images of dead white men’.

Her Ladyship’s description of her time on the top court, including, as I have said, the Brexit case (sometimes referred to as ‘the case of the decade’) is disappointingly short. But one sees her point in not wanting to reduce a life in the law to about nine years on the House of Lords and Supreme Court.

The motto of Lady Hale’s coat of arms as a Law Lord is ‘omnia feminae aequissimae’, which translates to ‘women are equal to everything’. Her life proves it.