The subject of this book is Pakistan; Pakistan and the deathly strangle of its blasphemy law, Pakistan and its disastrous tryst with al-Qaeda, Pakistan and its arid frontiers whose soil is still fertile enough for the flowering of the Taliban, Pakistan and its heroes and heroines willing to risk their lives for a country that repeatedly lets them down. For nine years, as a journalist with the Guardian and the New York Times, Walsh had the dream assignment of travelling around a country full of people, who, as he says, “wanted to talk”. ‘Nine Lives’ is the distilled essence of those conversations.

The concept – explain the place by delving into people’s worlds – isn’t new. We have seen it before in Suketu Mehta’s magnificent “Maximum City”. The similarity to Mehta’s work reaches its crest in the chapter on a policeman called Chaudhry Aslam Khan, an “encounter specialist” in Karachi. Aslam closely resembles Rakesh Maria, the Mumbai cop depicted in Maximum City. And yet, the difference is everything. Maria did not have to contend with the Taliban ramming a truck, packed with explosives, into his house’s gate. He did not, in the end, get blown up by a suicide attack featuring 200 kg worth of bombs strapped to a pick-up truck. The chapter is titled “Minimum City”.

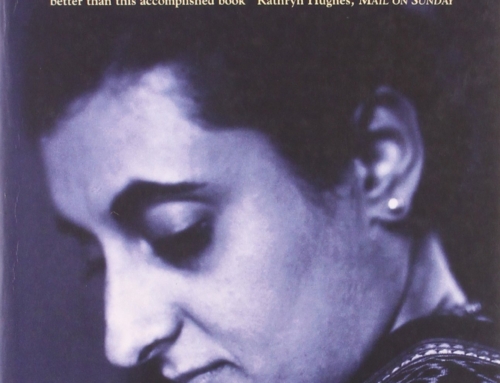

The enigmatic Benazir Bhutto makes a cameo, surviving one attack when she returns to Pakistan, and predictably succumbing to the next. Nobody knows who killed her, but everyone knows who destroyed all the evidence. After she dies, Walsh gets a chilling text from his ISI contact, “Read Julius Caesar again.”

Somewhere in the middle, while speaking of his experiences interviewing Pakistani officers posted in the benighted, lawless world of Waziristan in North-West Pakistan, Walsh deprecates the establishment view of Pashtuns as versions of the ‘noble savage’. The irony made me smile, since most of the ‘lives’ chronicled in this illuminating travelogue turn out to be nasty, brutish and short. As a reader, I was captivated, while faintly wondering why no one seemed to be dying of old age.

It must be said, though, that Walsh’s personal experiences in Jinnah’s Land of the Pure are far more varied, exciting and revelatory than his occasional lapses into Pakistani history. Here we find the grip slipping a little. No, Jinnah’s daughter never “married a Christian”, as Walsh seems to think. She married a Parsi. Jinnah was not “one of England’s most sought-after barristers”, as we are told; in fact, he largely failed at the Privy Council Bar, something his longtime colleague Justice M.C. Chagla tells us with relish in his own memoir. The reference to Justice Muhammad Munir of the Pakistani Supreme Court as “sagacious” made me chafe. Walsh either doesn’t know, or papers over the fact that in the 1950s, ‘His Lordship’ endorsed the odious “doctrine of necessity”, validating the imposition of martial law, and paving the way for decades of army rule. Justice Cornelius, the lone dissenter in that case, has a better claim to the word “sagacious”. When relating history, the problem with even a small inaccuracy is that it makes one question the whole.

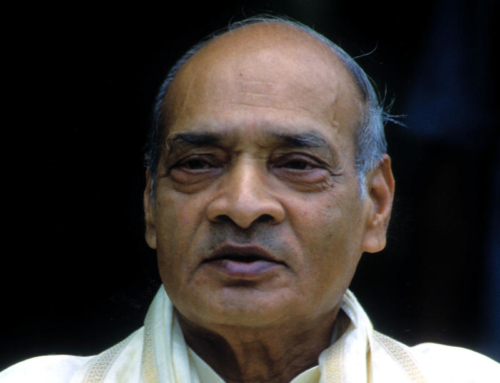

My favourite ‘life’, by far, was of the Balochi sardar, Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti. We are introduced to the Nawab as he is setting an English essay competition, with cash prizes, for his subchiefs, or waderas. Titles include “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned” and “Tides of life”. I found him endearingly mad. The knowledge that he settled disputes by making his men run over hot coals (it is believed that the person telling the truth doesn’t have charred feet) diminished my enthusiasm for him slightly, but only slightly. At the end of his life, and almost 80, we are told that he has led his followers into a suicidal war with the Pakistani government (which ends up killing him). In the book, he responds to foreign reporters questioning the prudence of this strategy by growling, “What more is there to life than love and warfare?”. An unanswerable question.

From the first chapter of the book, we are informed of the ending – ISI men kick Walsh out of the country. It turns out, finally, that this is for asking too many questions about Balochistan. In a book full of ironies and contradictions, we encounter one last one – the authorities are fine with reporting on global issues like terrorism and Kashmir, but cannot stand any meddling into their own, ‘secret’ war. Like his interviewees, ultimately Walsh’s life in Pakistan turns out to be nasty, brutish and short.