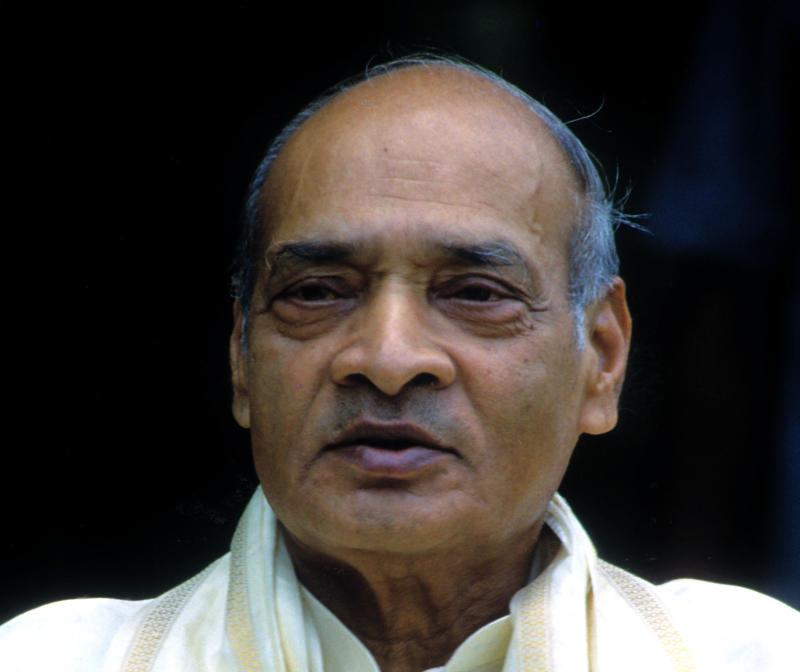

In her riveting three volume series on Thomas Cromwell, Hilary Mantel explores the wolfish ambition, feather-touch guile and unblinking sadism of the man who rose to become Henry VIII’s chief minister. Replace London with Lutyens’ Delhi, the king’s court with the Nehru-Gandhi durbar, and it is clear who our Cromwell was: except, unlike his forerunner, Narasimha Rao’s vaulting ambition did not lead to him losing his head – at least not immediately. For five stormy years, Rao took up the crown and himself became king.

Despite not being a formal historian, while writing this book, Vinay Sitapati displayed the spirit of enterprise that goes into making a good chronicler – he was able to impress Rao’s family enough to make them share his personal papers and, excitingly, the digital diary he maintained for a large part of his time in power.

The diary entry for 22 May 1991, the day after Rajiv Gandhi was killed, is particularly fascinating. Rao is at 10, Janpath, ostensibly mourning with other Congressmen around a coffin containing what fragments remain of Rajiv’s body. Yet, the jostling for the PM’s chair has begun. Pranab Mukherjee takes Rao aside and assures him that there was ‘general agreement’ on him taking over. Rao is delighted, but senses a trap: “Either [Pranab] was himself a dupe or he was party to some kind of design and was trying to lull me”. Decades in the Congress have taught him the pitfalls of showing too much ambition too easily. He remembers himself. He must retain the appearance of being paralysed with grief. So he acts diffident, and then suggests the name of an obviously unacceptable candidate, ND Tiwari. Of course, all the time, he is a spider, appearing immobile till the time to strike arrives.

Rao’s most consequential move as PM – opening up the economy and liberating hundreds of millions of Indians from the clutches of the licence raj – deservedly gets a big chunk of the book. Rao inherited an economy that was roughly where Sri Lanka is today, in red alert crisis mode, and propelled it to multidecadal growth. To do this, he had to deploy the full range of his skills as a politician. He lies in his presidential address to Congressmen, claiming that the new changes were a continuation of Nehru’s old policies. He deflects protesting members of the Left by bringing up the Babri mosque – surely they didn’t want the same pickaxe-wielding fanatics in power? He plays down the revolutionary policy abolishing industrial licensing by having it read out in parliament by a junior minister, and then heading off to dine with the Prime Minister of Mauritius.

For all his skills in managing policy shifts in New Delhi, Rao came up short in the only test that counts among politicians – he lost the election for his party. By then, it seems as if everyone was tired of him. He had riled up socialists (for obvious reasons), hurt his party by implicating several of his own colleagues in the ‘hawala’ scam, failed to protect the Babri masjid from being felled by a mob, alienated the Gandhis, and compromised his own integrity by bribing JMM MPs in order to retain power in a no-confidence motion.

Overnight, the defeated Rao was a nobody. To quote the last Mughal king, Dilli Zafar ke haath se pal mein nikal gayi. No one mourned his exit, and he had to cancel the tea party he had proposed when he demitted office, because no one confirmed their attendance. When he died, the Congress, now firmly under Sonia Gandhi, did not allow his corpse to be brought into the Congress Headquarters. Dogs sniped at his remains after the cremation.

The man who changed India had to depart unlamented and unwept.