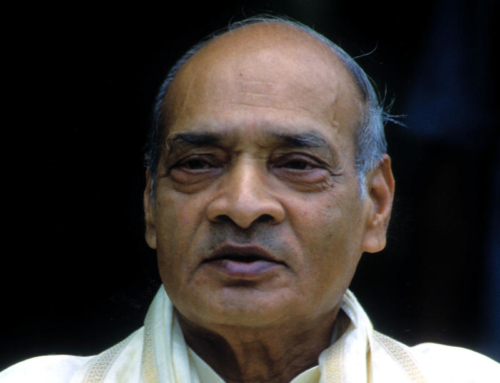

A review of ‘Mi Kasa Zhalo’ by Acharya Atre

The essays that make up this memoir, each one dedicated to a separate aspect of the author’s repertoire (writer, playwright, newspaper editor and so on) have one thing in common – they show us why Maharashtra fell for ‘Acharya’ Pralhad Keshav Atre, no matter what he tried. That mix of precise observation, rapier wit and unabashed pugnacity still has the power to make the blood race.

His rise to fame, I learned, was on the heels of the publication of a book of poems lampooning the clique of the dimly-remembered Marathi poet Madhav Julian and its self-conscious, Persian-heavy Marathi. Atre was to never forget this early encouragement from the public to punch and punch hard. The later shift to journalism and politics were natural transitions, once he had mastered the bucking horses of trouble-making and rabble-rousing.

Atre’s version of his origins in 1910s Pune makes for engaging reading. Though he calls the city depressing and frustrating (“even the brothels would shut at 8 pm”), his description grips the reader. The town comes alive with the growl of Tilak, the studious sallies of Gokhale, vivid accounts of the best eateries and misal joints, and an astonishingly rich portrayal of the theatre and poetry scene, all seasoned with Atre’s sprinkles of wit and humour.

The politics chapter traces an arc that begins with Atre’s championing of the Congress during the freedom movement. In his Congress years, Atre utilised his popularity among the public to become a municipal councillor. He headed the party in Pune. When he was roughed up by Savarkar loyalists during a speech in a college, Gandhi even wrote him a letter of solidarity. Disillusionment set in with the Congress leadership’s endorsement of the decision to partition India, a volte face from what Gandhi and Nehru had said for so many years. This book was written in the 1950s, and naturally, the narrative stops there.

We narrowly miss out on Atre’s pivotal participation in the openly anti-Congress movement to create a state for Marathi speaking people – the ‘Samyukta Maharashtra andolan’. Books bearing Atre’s speeches, editorials and articles during this movement, heavy with tales of incarceration and gunshots – wounds to the Marathi psyche that are stitched up with Atre’s impassioned ripostes – are still in vogue. The brutal repression and colonial savagery of the persons who were meant to have supplanted the British deserves to be documented, read and spoken of, and Atre’s contributions belong in the canon of this genre. The best account of Atre’s role in the movement is his own magisterial chronicle in the autobiographical ‘Karhe che paani’ (The Water of the River Karha).

Even when he was a politician, Atre was foremost an artist. Which is why the theatre and film sections in the book are instructive. There was a gilded time when theatre reigned in India and fans like Atre would sit in adjoining restaurants to save the cost of a ticket while listening to performances. The enthusiast evolved into a maestro in his own right, writing plays that are still performed, decades later. Atre is never one for modesty, a fault he recognises in the book, but his self-praise when talking about the success of his plays is particularly nauseating. This narcissism is somewhat tempered when referring to his more middling success in the film industry – but he did receive the President’s gold medal for his iconic Marathi film ‘Shyam chi Aai’, another staggering achievement – and makes sure we know it.

Among his diverse feats, less remembered are Atre’s contributions in education. In his early 20s, he was appointed as headmaster of a badly-run school in Pune. Making the best of a bad hand, he was able to transform the standards at the institution, generating enough popularity and goodwill to engineer the removal of the existing trustees and have himself and his associates installed in their place. Under the new management, the school flourished, a new building was built, and a separate school for girls (a new concept) was also started. Atre would have gone on to become a stellar educationist, had politics and filmmaking not beckoned.

The book ends with an essay titled ‘Who am I’, which contains Atre’s analysis of his journey, and of life. The point of existence, he reckons, is to always pursue joy; to fill life’s cup with overflowing vitality. Like the conman protagonist of his famous play, ‘To Mi Navhech’, Atre lived multiple lives in his one life. It is difficult to replicate that polymath brilliance. But we too can learn from his example by intermittently shaking ourselves down, conquering our inertia and changing paths.