The first time I came across the name was in 2007, in the pages of Time magazine. As I remember it, the presidential election was next year, and the probables for the Democratic ticket were listed, with two lines given to each. Under the likeness of the senator from Illinois, I read that this candidate would have problems getting elected because his surname sounded like Osama. At the time, this seemed logical enough, and anyway, what were the chances of a Black man becoming President of the US? I simply assumed, as most did, that it was Hillary Clinton’s moment.

‘A Promised Land’ is Barack Hussein Obama’s account of his rise from a virtual nobody to the most powerful man on the planet – an irruption of idealism, eloquence and ecumenism into a world that is ravaged by the mistakes of its only superpower – mistakes of war, mistakes of prejudice, and mistakes of financial greed.

The euphoria doesn’t last. After his heady propulsion to the top of the tree, all wide grins, kisses with Michelle, and soaring rhetoric, the new incumbent quickly realises that the “hopey changey stuff” (as Sarah Palin called it) couldn’t get bills passed, save lives, or change the system. The presidency, he is told by an advisor, is like a new car – it starts depreciating the minute you drive it off the lot. Coming to power was the easy part.

Straight off the bat, Obama signs an executive order to shut the military detention centre (“torture cell” would be a better description) at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, the existence of which is the US’s longstanding shame, and an insult to the Geneva Conventions. Later, he finds himself floundering over the question of what to do with its detainees – Release them? Repatriate them to their home countries? Bring them to the US to face trial? Needless to say, ‘Gitmo’ never shut, and is now open indefinitely, on account of another executive order, signed by Obama’s successor.

Implementing executive orders may be hard, but at least the President gets to sign them. Shepherding legislation through Congress, we learn, is almost impossible, thanks to a kooky rule followed in the US Senate (Obama calls it “the headache of my presidency”). I was only faintly aware of the US Senate’s “filibuster rule” till now. After reading this book, I learned that if the electoral college system is outdated and undemocratic, the Senate filibuster is positively anti-democratic. Apparently, it’s not good enough to have a majority in both the House of Representatives and Senate (as the Democrats did in ’08). A bill cannot pass the Senate unless 60 of its 100 members vote for it – anything less, and the bill’s opponents are entitled to continue speaking till eternity, scuttling all legislative business. This absurdity makes bold legislation on critical issues like healthcare and climate change virtually impossible. Obama’s problems metastasise when the Republicans take the House of Representatives in 2010.

The former president smoothly wends the narrative through the outside world and the world of his mind. One of the better aspects of this rather long book is Obama’s description of his decision-making process. He is right to have included some of these bits in the excerpts given to the press for publication. The book invites us to be seated in the Situation Room in the White House, watching Obama wrestle with thorny issues like the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Arab Spring, and the financial crisis. In each case, the President shows a commitment to working towards precisely-defined goals, an unwillingness to blindly defer to the judgment of experts, and an understanding that beyond a point, he has to just trust his instinct. This approach, imbued with thoroughness and tenacity, helps explain the many correct decisions he took to ascend to being First Citizen. The sessions with Pentagon officials are especially impressive. Obama is clear in his mind that he would not be following the Bush administration policy of “doing what the generals say” (all they seem to advise, incidentally, is sending more troops in). He challenges the men in uniform, makes them go back to the drawing board, and even has an independent Afghanistan expert conduct a review of the situation in that country. In all this, he is supported by Joe Biden, who seems to have decided that he would never take heads of armed forces at their word after he was misled into supporting the war in Iraq (his advice to the President: “Listen to me, boss…Don’t let them jam you.”) The US commander in Afghanistan, Stan McChrystal, nastily refers to Biden as “Bite Me” (he gets fired for the quip). Hillary Clinton is the opposite. Obama cites her “hawkish instincts” and political background as the reason why she was “perpetually wary of opposing any recommendation that came from the Pentagon”. This contrast made me feel that between Biden and Clinton, perhaps the right person made it to the White House. On the other hand, Biden’s suspicion of US intelligence makes him even oppose the Abbotabad raid on bin Laden’s mansion, sharply demonstrating the disadvantage of his pacifist leanings.

An intemperate, snarling Donald Trump appears in a non-descript suburb of the book, hurling wild accusations about “birtherism” – the theory that Obama was born in Kenya and was therefore ineligible to be an occupant of the White House. This is, of course, racism in all its rawness, all its blindness, shaking its fist and waving its pitchfork at the Black man. Trump even questions Obama’s authorship of “Dreams From My Father” (his point – someone of Obama’s calibre could never have written it). I would be tempted to ignore, and struggle to remember the brief vignette of this hateful madman, had it not been for what we know happened next.

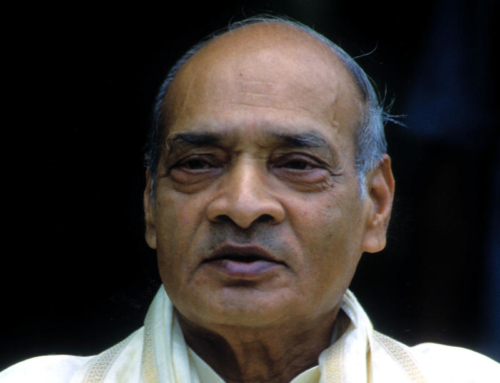

As an Indian, I was curious to know what Obama thought of the country, and our political leadership. His verdict on the class of 2010 (the year he visits) – Manmohan Singh is uncommonly decent, Sonia Gandhi is the kind of person that would use an audience with the US President to advertise her son, and the son…is incompetent. No surprises, then. He also mentions the BJP’s “divisive nationalism”, whetting the appetite for the next volume, when I presume we will learn what he really thought of Narendra Modi. On Obama’s last visit here, which was after his presidency, he was frustratingly bland with his utterances at public meetings, even refusing to condemn Section 377 and the criminalisation of homosexuality. I suppose the discipline of the written word is better for keeping a man honest than the thrill of a live audience, which brings with it the urge to be loved – an inextricable part of Obama’s personality. More relevant to India than anything Obama musters is what that great democrat Vaclav Havel whispers to him when he visits Prague, “Today, autocrats are more sophisticated. They stand for election while slowly undermining the institutions that make democracy possible. They champion free markets while engaging in the same corruption, cronyism, and exploitation as existed in the past.”

Many reviewers have praised the writing style. It is light, descriptive, and teems with attention to detail. The book begins with an elegant essay on the West Colonnade in the White House – I assume this bit was put in to assure the reader that the 44th President writes well, and despite the book being long, the journey will be worth it. Quite right. The only false note I heard in the whole book was this sentence: “[Sarkozy and Cameron] showed barely disguised relief that we had handed them a ladder with which to get down from the limb they’d climbed out on”. Yuck.

Obama saves the most electric part of the tome – the planning and execution of the bin Laden assassination – for the last. The killing of a person in the middle of a city, at walking distance from the Pakistani version of the National Defence Academy, without the knowledge or prior consent of the government, in a huge bungalow protected by high walls and barbed wire. Incredible. In one of the opening chapters of the book, Obama criticises the “dual fiction” that the Bush administration maintained – that Pakistan was a reliable partner in the war against terrorism and that the US never encroached on Pakistani territory in the pursuit of terrorists. With that one act, both fictions were discarded.

This is a particularly topical read, since our present times seem so much like 2008. The world is in a shambles again. Once again, the US has voted in a new President to pick up the pieces.